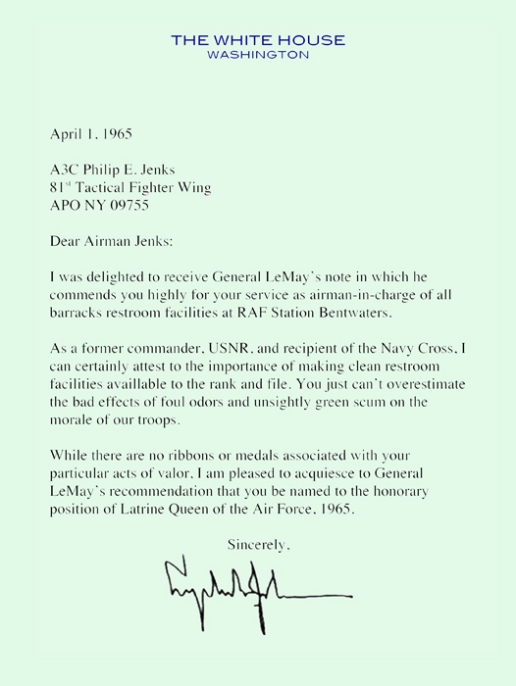

April 1, 2014. This previously undisclosed letter from President Lyndon B. Johnson requires some explication.

To make a long story short, I was the best Latrine Queen in the Air Force.

Anyway, that’s what Curt LeMay said. Just ask him.

Oh, right. He’s dead.

But you can believe me.

It all began in October 1964. I was in basic training at Lackland Air Force Base, Texas, struggling to find my niche in the military hegemony.

I got a nearly perfect score in the Air Force aptitude test in mechanics, achieved by guessing my way through several pages of multiple choice questions, and I tested high in typing. Early on, it looked like I’d be spending four years repairing jets or typing supply requisitions. Neither possibility seemed heroic (although as I think about, it’s improbable that jets maintained by me would stay in the air long enough to liberate the Mekong Delta). I began to question whether volunteering for military service had been such a good idea.

Then one morning Sergeant Ellefson, our barracks chief, said he detected stubble on my face. This was likely a ruse because, at 18, I had never shaved a day in my life, but sergeants had a highly personalized view of reality and it was rarely a good idea to challenge it. So I checked an impulse to stroke my fuzz-free cheeks and said, “Yes, Sergeant.”

“And this is what I’m gonna do about it,” Ellefson said. He led me into the barracks latrine – a room equipped with an open-bay shower, 12 sinks and two rows of redolent commodes facing each other – and said the words that would change my life.

“You’re gonna be my Latrine Queen,” Ellefson said. “And every morning I wanna see these commodes so clean General LeMay can eat breakfast out of ’em.”

Ellefson didn’t seem like the kind of guy who used hyperbole, so I said, “How does he like his eggs?”

“You’ll find out,” he said, and left me alone in the Latrine.

It is now almost forgotten that Curtis E. LeMay was the Air Force chief of staff. He was a hard-nosed S.O.B., the father of the Strategic Air Command, and the World War II commander who oversaw the destruction of Japan from the air. Later, he applied the same strategy to North Vietnam.

I was stunned when Sgt. Ellefson strode out of the latrine, leaving me alone with so much stained porcelain.

But I had grown up in a household where clean toilets and godliness were theologically fused and I knew exactly what to do. I armed myself with sponges, scowering powder and cans of pungent disinfectant and set to work. By the end of the day, my nose smarted with lingering fumes of ammonia. More to the point, the harsh glare of white porcelain that glowed like our transfigured Lord, brought tears to my eyes.

The next morning, Sgt. Ellefson’s mouth dropped open when he came into the latrine.

“God DAMN,” he said. “God DAMN.”

He stroked the silvery faucet of one of the sinks, and admired his unblemished reflection in one of the mirrors. He stepped back to view the full pristine panorama and he began to smile. “God DAMN.”

Sergeant Ellefson placed me on full-time latrine duty. That was fine with me because it replaced the more onerous trials of boot camp, like precision drilling and olfactory comparison drills to prove you could tell the difference between tear gas and human pheromones.

And politically, Latrine Queen proved to be an extremely powerful position. It gave me the authority to impose such time-saving measures as requiring my barracks mates to use the latrines in the mess hall and shower in the rain.

But as the eleven weeks of basic training neared at end, I began to worry what the next four years might hold. There were no medals for exceptional commode cleansing, nor did a four year career of urinal polishing seem likely to generate diverting tales to spin in American Legion bars.

Then one day as I was using a cotton swab to clear calcium deposits from the shower heads, I heard a commotion in the barracks. A high-pitched voice yelled, “Ten HUT,” followed by a thunderous rumble as fifty guys leaped off their bunks and slammed their brogues on the linoleum floor.

“Where’s the latrine?” a gravely voice shouted with urgency. “Gotta crap.” This was not an unusual occurrence in San Antonio where northeastern stomachs were introduced to green sausa and burritos. After lunch, stricken officers often found it necessary to pop into the first barracks they passed.

“This way, Sir.” Ellefson’s muffled voice sounded uncharacteristically polite.

“Outa my way, goddam it.”

The latrine door sprung open and in marched a scowling officer clenching a huge Cuban Cohiba in his teeth – unusual even in the earliest days of the Cuban economic boycott. The officer was barrel-chested with thick steel-gray hair. There were four twinkling silver stars on each of his shoulders.

Before I could stammer, “General LeMay, Sir,” he pushed me out of his way and moved earnestly toward the bank of sparkling commodes. But the unblemished souls of his spit-shined low-quarter shoes were too new to resist the polished tiles of the cleanest latrine in the Air Force.

Down went the general.

I watched transfixed as the general’s feet rose and his posterior descended in a fluidly graceful motion, while his arms shot out like a uniformed cruciform.

Abruptly, he was on his back with his limbs fully extended like DaVinci’s Vitruvian man. His wide body spun in a clockwise motion on the shiny floor.

The general’s gabardine uniform offered little resistance to the polished tiles, but when he stopped revolving he surrendered the back of his head to the hard floor. He appeared to be carefully assessing his situation, like the great tactician he was.

I could think of no chapter in the USAF Customs and Courtesies manual that addressed this particular situation. I stood cautiously over the general and leaned forward to make eye contact with him. He scowled upwards at me, furiously chewing the Cohiba.

“General LeMay,” I ventured.

The general narrowed his eyes menacingly. I think he said, “Grempf,” but he might have been swallowing a piece of tobacco.

“How do you like your eggs?”

He appeared to think about it briefly, but then he spat the wetly chewed cigar out of his mouth so forcefully that it smacked against a urinal on the far side of the room.

“Help me up, goddam it. Gotta crap.”

I placed my hands under his arms and pulled him to his feet. As soon as he was erect, he shoved me aside and skidded toward the commodes. He dropped his gabardine drawers and plopped down on the seat. I had gotten used to seeing young basic-trainees seated in the humiliating ritual of collective crapping, but the Air Force chief of staff seemed out of place.

The general carried it off with dignity but never stopped scowling at me. I wasn’t sure what the rules called for, but I assumed they had something to do with standing at strict attention. I refrained from saluting.

Soon (and I spare the reader the auditory and olfactory details of the scene) the general was finished. He stood and tightened his belt.

General LeMay walked to one of the sinks. As he washed his hands he looked around the cleanest latrine in the Air Force.

“Goddam,” he said. “This must be the cleanest latrine in the Air Force.”

Now seemed like an appropriate time to salute. I snapped my right hand rigidly to my forehead, and he responded with a more casual gesture that looked as if he were shooing a fly from his face.

Silently, the general pulled a neatly folded towel from the shelf and dried his hands. When he walked out, I picked up the reeking cigar butt and threw it away.

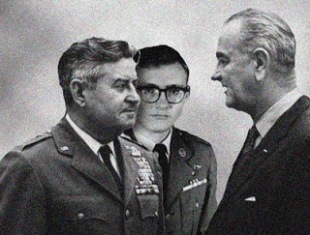

General LeMay retired from active duty early in my Air Force career, and I saw him rarely after that first latrine rendezvous. When I did see him, it was usually when the chief of staff was called to accompany President Lyndon B. Johnson on his visits to military installations. For the remainder of the general’s career, whenever word came down that LBJ was planning to visit a base, I got a call from a chief master sergeant in the chief’s Pentagon office.

General LeMay retired from active duty early in my Air Force career, and I saw him rarely after that first latrine rendezvous. When I did see him, it was usually when the chief of staff was called to accompany President Lyndon B. Johnson on his visits to military installations. For the remainder of the general’s career, whenever word came down that LBJ was planning to visit a base, I got a call from a chief master sergeant in the chief’s Pentagon office.

“The old man wants the President to have access to the cleanest latrine in the Air Force,” the sergeant would say. “Get to work.”

On such occasions I would spend a week getting the presidential latrine in shape for presidential elimination, whichever form it might take. On occasion, General LeMay would invite me outside to shake hands with the president.

“Goddam,” LBJ would say. “That must be the cleanest latrine in the Air Force,” and General LeMay would nod happily. I would stand modestly between the two men, trying not to expose the pride that was swelling in my chest.

But pride was warranted. I was the best Latrine Queen in the Air Force.

Anyway, that’s what Curt LeMay said. Just ask him.

Oh, right. He’s dead.

But you can believe me.

April Fool that I am, I trust no one besides Zelig and Forrest Gump, except YOU, of course. History is written by those who outlive those about whom they are writing.

Pretty shitty story.